- Home

- Dudley Lynch

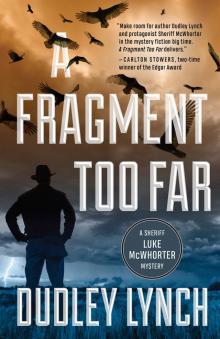

A Fragment Too Far

A Fragment Too Far Read online

A Fragment Too Far

A Sheriff Luke McWhorter Mystery

DUDLEY LYNCH

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

To my family.

One and all.

Chapter 1

My working eye — the other one was plastic — kept telling me I’d witnessed the world’s first buzzard-cide. Or something akin to it. The bird’s precipitous plunge had looked choreographed by the grim reaper.

The spectacle had unfolded not far below where I was parked — a turnout near the western end of the O’Mahony Ridge. This chain of boulder-and-brush-covered peaks ran for forty miles through the middle of Abbot County. The stricken buzzard had disappeared from my view beneath the stunted live oaks and mesquite trees at the point where the prairies ended and the ridge began. To the north, short-grass prairies stretched to the horizon, silent and empty. Usually, they spread out beneath cloudless skies.

At first, all I’d noticed was a kettle of the birds taking lazy swirls on one of our summer thermals.

Then this bird had veered away from the others. Flown two tight circles on its own. Stretched both wings. Drawn its feet and scrawny neck close to its body. Remained motionless for a second. Tipped backwards. And plunged straight to the ground.

You’d have thought the ill-starred bird had been attached to an anvil. Its fall was as true to vertical as a plumb line.

But a deliberate act?

I decided not.

More like an act of God. The animal shouldn’t have been flying. Period.

Thinking about it, my inner choirboy dredged up a snippet from an old hymn: “Nevermore to roam. Open wide Thine arms of love, Lord, I’m coming home.”

It wasn’t unusual for me to think of old hymns. Or sermon titles. Or Bible verses. I was probably the only sheriff in the country — maybe the world — with a divinity degree from an Ivy League school.

Mine was from Yale.

Pretty expensive training for a sheriff. For certain, this isn’t the kind of background you’d expect for a West Texas county’s chief law officer. Or, in all likelihood, any other Texas county’s. But then, I was used to explaining how my whole post-high-school educational experience had been shaped by the idea of being a preacher. When people asked me how I’d ended up being Luther Stephens McWhorter, sheriff, instead of Luther Stephens McWhorter, minister of the gospel, I’d tell them it was a long story. One probably best saved for another time.

Was it because of the pain?

That was part of the reason.

But it was more because of the risk.

You can’t put much of a foundation for a new future in place if you keep obsessing over what you’ve lost.

I pushed those thoughts aside to concentrate on what I was seeing through my windshield.

The sight bordered on the majestic — if you were looking into the distance. Red-dirt prairies meet green treed hills meet endless azure sky. But the closer you looked, the more imperfections you saw. Scraggly trees meet yawning gullies meet rock-strewn grasslands. Only the azure sky carried over. One of my deputies had a puckish name for this whole area: “No Country for Old Radiators.”

It was the vastness I loved about the country. And the isolation.

I could creep up the rutted gravel road, park my vehicle, and unpack my lunch. Ease my seat back when I finished eating. Watch the clouds drift by — if there were any clouds to be had. Luxuriate in the solitude and the stillness. And, most times, enjoy a nap.

On this blistering-hot day, it had almost worked that way.

I’d savored my ham-and-cheese sandwich, corn chips, and slice of store-bought orange spice cake. Peeled and nibbled down a banana. Poured myself more iced tea from my battered Stanley thermos. Directed the car’s AC away from my face. Made a minor adjustment so my seat was less erect. And tried to decide whether to gawk or snooze.

But my thoughts wouldn’t stay away from the buzzard.

I returned my seat to its upright position. Stepped outside to relieve myself. Brushed a few cake crumbs from my lap. Slipped back under the steering wheel. And aimed my souped-up Dodge police cruiser off the ridge.

I thought I knew where the buzzard had landed, and I wanted a closer look.

* * *

The turnoff was less than a minute away. By the first “welcome mat” on the left. Not that a cattle guard is that welcoming. The metal devices are like small bridges pockmarked with holes. If a bull were to misstep on the ugly grids, the animal could break a leg faster than a cat’s slap. Hit one of the contraptions too fast in a vehicle, and you could destroy a transmission or oil pan. Or lose a few teeth.

I crossed this one at a prayer’s pace. Started inching up the weed-choked road’s twin tracks. Spotted a small whitetail deer through the live oak and mesquite trees. And prepared for my first glance of Professor Huntgardner’s enigmatic old house since longer than I could remember.

No one lived there now.

The professor was — what? — almost ninety. They’d moved him to an old-folks home some years back.

His sizable house was odd. Always would be. Not because it looked odd. In many ways, though it was showing neglect, the boxy, cinnamon-brick, two-story house was still picture-perfect. In town, it would have fit well into any upscale neighborhood built in the 1920s or 1930s. In part, that was because of its deep, wraparound front porch, edged

with low brick half-walls. The Huntgardner house looked odd because it was much too grand an abode to be so far out in the boonies. It was thirty miles from anywhere, and that was by gravel road. That nearest “anywhere” was Flagler, our county seat.

The professor’s place of employment hadn’t been any closer. The University of the Hills was one of three such institutions we had in Flagler. All were church-sponsored schools of modest enrollment. They were one of our two main claims to fame. The other one was the man now living in the White House. President Jim Bob Fletcher — James Robert, to anyone from outside Abbot County — had grown up here.

I’d once been a student in one of Professor Huntgardner’s physics classes. Not a very good one — student, that is. I’d gotten my only F in two decades of schooling from Professor Thaddeus Huntgardner.

My dad had known Huntgardner too. After both of them had retired, I’d driven “Sheriff John” out to the Huntgardner place a time or two. And I’d been to it on a few other occasions.

But none of those visits had sent a morbid rewrite of verse 4 of Psalm 23 rocketing through my mind.

This one did.

Yea, I have walked into the darkest valley, and I have seen all evil . . .

Chapter 2

The nose often announces death before the eye can register it. For chemical reasons.

Putrescine and cadaverine, to name two. Powerful smells produced by decaying animal matter.

Think rotting meat bubbling in cheap dime-store perfume. Then imagine that smell a hundred times fiercer. Feel the stupefying stench as it coats your nose hairs, tongue, the back of your throat. Realize that holding your breath won’t help. By the time you detect the unspeakable nastiness in the air, it’s already seeped into your lungs.

I’d smelled decomposing flesh more than a few times as a law enforcement officer.

But I’d never lost my cookies.

Until now.

I braked hard and managed to get my door open part of the way.

Too slow.

I puked much of the packed lunch I’d eaten only minutes before onto my raised car window. Then staggered out of the car. Pivoted in a half-circle. Managed to put both hands on the front car fender. Leaned forward just in time to carpet-bomb the fender with more of my lunch.

The buzzards had been puking too. And peeing. And pooping. Mostly on themselves. As any rancher’s kid knows, this helps to cool them off — and causes them to stink to high heaven. The white streaks on their legs and feet were from uric acid of their own making.

But this wasn’t what was causing my distress. The horrendous smell had triggered that. Plus, realizing what the buzzards were feeding on.

Human remains.

The corpse closest to my car sprawled at the base of the short concrete stairs ascending to the porch of the house.

A half dozen buzzards milled around the prostrate body. When the buzzards weren’t pecking at it, they were jostling each other. This allowed me only occasional glimpses of the victim’s bloodied ribs. The denuded arm and leg bones. And the mangled areas where the face and scalp had been.

In two places in the porch shadows, beady-eyed black-and-red heads were popping up. Disappearing. Reappearing. Then vanishing again.

Over and over.

The knee-high brick shelf around the porch’s edge kept me from seeing what had these birds so preoccupied. But from the way they were strutting and bobbing, my guess was the shelf was shielding two more victims from my view.

A fourth corpse lay draped across the open space framed by the front-door threshold. The body lay on its side, half-facing the yard. Or rather, its bones did.

What was left of one decimated arm angled upward, blood-stained as a butcher’s stash. The face was gone, picked clean. The torso, nearly so. Jagged holes had been pecked in the back of the victim’s eye sockets.

Other much smaller forms lay prone in the yard. More buzzards — deceased. A few were being eaten by their cousins. One of them could have been the one I saw fall out of the sky, the one I had followed.

I needed to sit down.

Breathe.

Think.

I wanted to consult someone, and I knew whose voice I wanted to hear.

But before that, I had to do something about my mouth. I reached for a bottle of water. Unscrewed the cap. Took a careful sip. Rinsed. Spat it out.

Another sip. Another rinse. More spitting.

Now I could risk a swallow.

I vomited again, this time on my car seat.

Fortunately, it was only a trickle. I wiped it off with a paper napkin left over from my lunch. Eased back into my seat. Rested my heavy arms against the steering wheel. My weary head followed, and I’m not sure how long it stayed there.

I needed to call my dispatcher at the Abbot County Sheriff’s Department. But first, I wanted the comfort and reassurance of the special agent in charge of the Flagler field office of the FBI.

I managed to push the right buttons on my phone. Didn’t know what I was going to say until I said it.

“Love you.”

Chapter 3

“Hold a sec, cowboy.”

Special Agent Angie Steele didn’t wait for a response. I’d violated a rule we’d both agreed on. Work stuff public, personal stuff private, and never the twain shall mix.

Addled as my mind was, I knew what Angie was about to do. Her office sat near one of the two front entrances to Flagler’s two-story, art-deco-style federal building. She would steer for the nearest door. Bound down the short concrete stairs with her blond ponytail flying. Veer west on the sidewalk. And walk until she had some privacy.

This time, her tone was a bit sharper. “Sheriff Luther Stephens McWhorter, this an official daft day for you?”

This was my chance to give her information she could ponder. Advise me about. Follow through on.

Not able to manage a complete sentence, I supplied her with a word. The voice offering it sounded weak and remote. I had to think for a moment about whom it belonged to. She would have to decide whether to treat my word as a noun, verb, or adjective. And whether it was of any use to her.

“Puking.”

Her reply skipped a beat but only one. “Tell me where you are.”

Again, my battered mind didn’t supply her with much to work with. “Smelling it.”

She knew she needed to know more. “Smelling what, gentle one?”

There it was. The caring that lay under the tough outer shell of my Glock 22–carrying girlfriend. She was younger than me, so much so that some of my friends said I was robbing the cradle. I disagreed. I’d been born in 1977, so I was only eight years older. That isn’t a chasm. We’d not even found it a distraction.

I wanted to tell her more, something useful, but I seemed to be flinging my words like errant paintballs. “Stink sticks.”

At this point, a typical agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation might have sighed from exasperation. But my FBI agent took charge.

When she learned I was sitting in my car, she asked if I could drive.

I told her not far. And not fast.

She instructed me to start driving away from the smell. When I could breathe good air, I was to stop and tell her where I was.

I thought I could make it to the cattle guard, and I did. Rolled up to the ribbed crossing grid. Pulled off to the right of the heavy iron fence posts and stopped a yard or two short. Put my patrol cruiser in park. Rolled down my window.

And heard the shots.

Someone back toward the house was firing a gun.

More shots.

Angie heard them over my phone. She again demanded to know where I was.

This time, I told her. She instructed me to keep my doors locked and the line open. She came back on twice to ask how I was doing. The third time she spoke, she said she was in line right

behind my chief deputy. Both were speeding past the western Flagler city limits on County Road 16. Twenty-five minutes tops and they’d be here.

But the muscular four-wheeler raced up long before then. The big-tired vehicle was covered in orangey-red dust, courtesy of our West Central Texas clay prairies. The three teenage boys in the vehicle looked grim.

The driver was almost too big to fit behind the steering wheel. The other two were standing in openings in the roof. Each clutched a rifle with one hand and clung to the vehicle with the other.

The driver braked the vehicle to a stop a few feet short of the cattle guard and pointed back toward the house. “Ho-lee crap, mister! Buzzards are eating people back there!”

My thought wasn’t the most sheriff-like.

Not my problem.

Then everything went black.

Chapter 4

The perspiring face hovering over my car seat was squarish. Huge, like its owner. And framed by a massive, high-crowned, brownish felt cowboy hat. The brim seemed to stretch straight across its wearer’s forehead from one ear to the other.

It was a man-child’s face, until I got to the burnt umber eyes peering at me through narrow slits. Why did I feel those eyes gave you the answers you needed only if you knew the right questions to ask? And maybe not then?

“Mister, you need to sit up and drink this.”

It was one of those sports drinks that rehydrate. The bottle was cold and the taste sweet, although I knew this was masking a lot of salt. After all, that was the point.

I drank everything in the bottle, and he handed me another one. Cold and salty-sweet and reassuring like the first.

I felt like I should be asking questions. But the lineman-sized driver of the SUV got his in first. “You been to the house?”

I nodded. “Just long enough to be sick.”

My caretaker-angel wasn’t missing much. “Looks like you just ate.” The snow-plow-shaped nose twitched. “Could be vasovagal syncope, you know.”

“Vasso-what?”

“Sorry, sir. My dad’s a doctor. Some people’s blood pressure drops, and they throw up when they see a bad injury or something. That’d explain why you weren’t out longer too.”

A Fragment Too Far

A Fragment Too Far